Good morning Bedford…We have casualties.

These words greeted 21-year-old Elizabeth Tease at 8:30 in the morning on the Western Union teleprinter. And with them, a community of about 3,200 fell to its knees. “Bedford was a quiet little town,” said Tease. “Everyone’s heart was broken.”

Disclosure: Some links on our site are affiliate links. If you purchase a linked item, we will make a commission, at no extra charge to you.

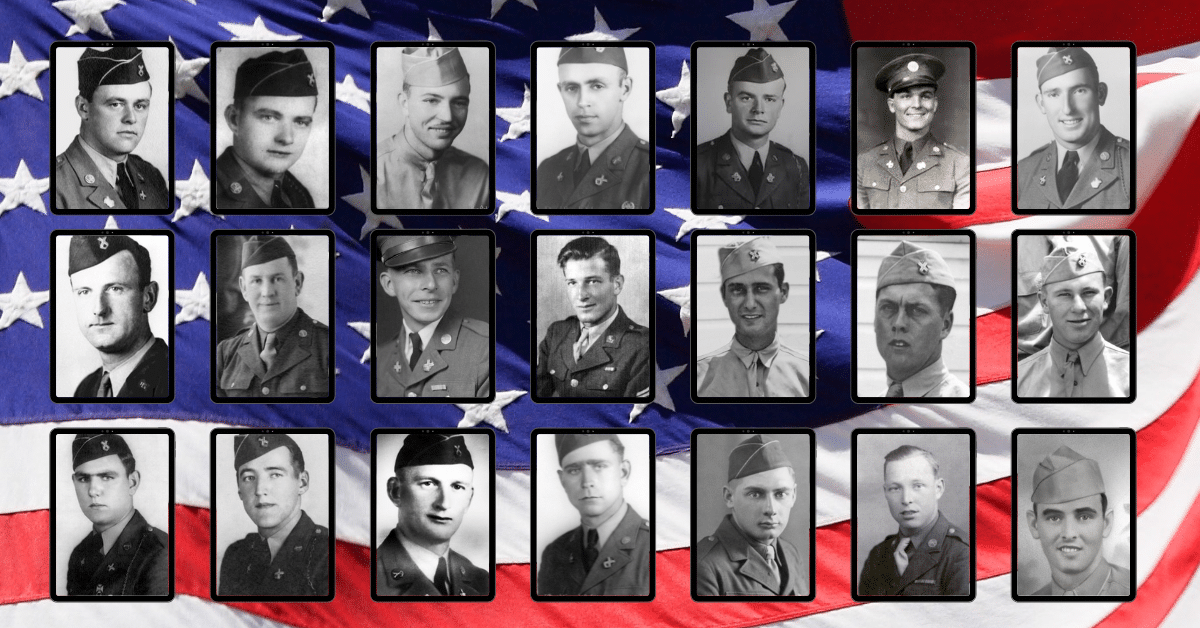

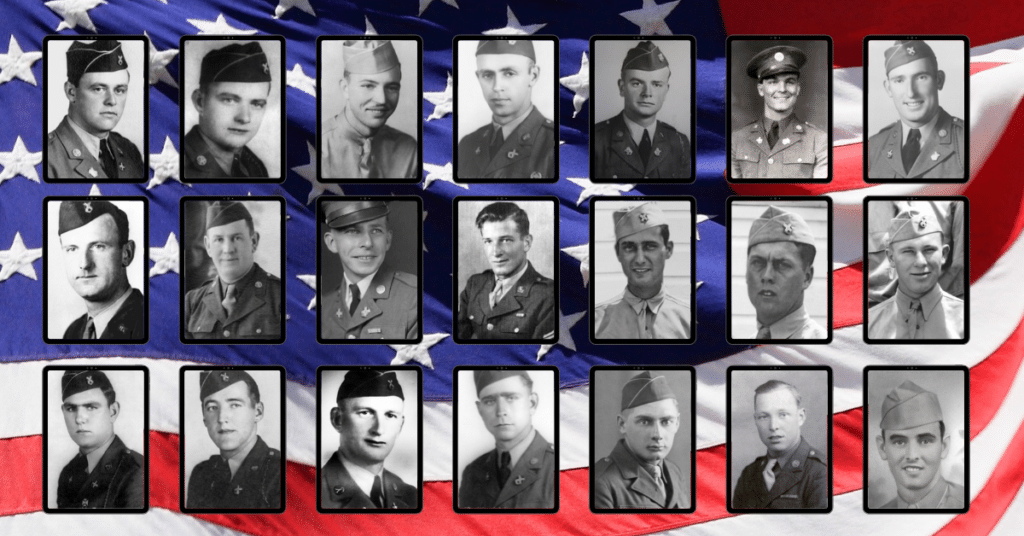

They were brothers. 3 sets actually. Bedford and Raymond Hoback. Earl and Joseph Parker. Ray and Roy Stevens. A young father, Earl Parker, would never meet his daughter. Bedford Hoback never got to marry his fiance, Elaine Coffey. Roy Stevens remembers speaking with his twin brother Ray. As they loaded onto the landing crafts, Ray reached out to shake his brother’s hand. “No,” said Roy. “We’ll shake hands in France.” These brothers never again saw each other. These words would always haunt Roy.

Twenty-six-year-old Earl Parker, a light-hearted and easy-going man, was madly in love with Miss Viola Shrader. Viola was one of the prettiest and most popular girls in Bedford. They married in 1940 and were eager to start a family as soon as possible. He had a job at the Piedmont Label Company, making labels for canned goods. He had no clear idea what he wanted to do other than get a job that paid money. Before leaving, Viola told Earl, “I don’t know how you’d go shoot anybody.” Earl shrugged in reply, “If it’s me or them, I guess I’ll have to.” Shortly after Earl left for war their daughter Mary Daniel Parker, “Danny” for short, was born. The night before the invasion, he was talking with his friends on the deck of one of the ships. Earl told his friends, “If I could only see my baby daughter, I wouldn’t mind dying.”

Twins Ray and Roy Stevens were inseparable. Sharing “everything except women.” Two of fourteen children, they attended a one-room schoolhouse. Later, the two find jobs to help the family through the Depression. Having learned to box at an early age, they would regularly fight to earn a few cents. Sometimes against one another. Roy worked on the production line at a mill called Belding Hemingway. One of the town’s largest employers. Ray worked in a grocery store. After work, they were always seen together. Roy would recall, “A twin is a little bit different than an ordinary brother or sister. They depend on each other a lot more. We were close.” They even bought a dairy farm together in 1938.

Grant Yopp lived and grew up with the Stevens brothers from the age of 13. The Stevens took him in after his own father deserted his family. He left his young wife and family when he left for war. His sister Anne Mae Stewart said he could have avoided the invasion because he was in the hospital. “But he left his room, put his clothes on, and went with the guys. He wanted to go.” He served as the leader of a mortar squad and was killed by enemy fire after landing on Omaha Beach.

Bedford Hoback had an outgoing personality and easily made friends. He acted like he was a carefree ladies’ man, but everyone knew he was devoted to his fiance. He served in the Regular Army before joining the Guard, being stationed in Hawaii. As soon as he returned home, though, Elaine ditched her previous boyfriend for him. They had always wanted to be together and were childhood sweethearts. His brother Raymond was quieter and more reserved. A religious man, he could always be found with his head in the bible. After eighth grade, he left school and started working for the highway department. He made enough money to buy a $750 two-door Chevrolet and loan his sister money for beauty school. Before leaving for war, Raymond worked for Rubatex in town. Both would die that morning with Raymond’s body never being found. The only remnant was his bible. Scooped up by another soldier who mailed it home to Raymond’s family. When Bedford’s mother had the opportunity to bring his body home, she decided to leave it in Normandy. She said they wouldn’t separate in life, so she wouldn’t want to separate them in death.

Frank Draper Jr. worked for Hampton Looms, the town’s largest employer. He was a standout on the company’s baseball team. Another of Bedford’s baseball greats was Elmer Wright, the son of the deputy sheriff. A hard-throwing right-handed pitcher, he signed a professional contract with the St. Louis Browns in 1937. A contract he hoped to fulfill after the war. Originally from nearby Roanoke, catcher Robert Marsico made a name for himself on his high school team. A job with the Piedmont Label Company brought Robert to Bedford. It wasn’t long before he, too, was a standout on his company baseball team. Of the three, only Robert Marsico would live past the initial wave on June 6th. Due to the injuries, he sustained in combat, he would never again play baseball.

Taylor N. Fellers was a bridge construction foreman with the Virginia Highway Department. A coworker of Taylor remembered him as “industrious, competent, and thoroughly reliable.” This is why it’s no surprise he skipped out of an Army hospital to make the landings. A serious sinus infection threatened to sideline him, but he had to be there for his boys. “I trained you and I’ve come to die with you if that’s what it takes.” The anxious men under his command felt a little relief to have their leader back. Sadly, he didn’t make it much farther than the beach. He was one of the first men to land on Omaha Beach from the sea. He had written home earlier about his men: “I’m beginning to think it’s hard to beat a Bedford Boy as a soldier.

John Wilkes and John Schenk were killed near the waterline. Hit by enemy snipers. Never again would John Wilkes drive his tan, wood-paneled station wagon down Main Street. Never again would he and his friends take their dates out to a picnic on Smith Mountain Lake. John met his wife, Betty, at a basketball game. They enjoyed bowling and dancing. John Schenk first met Ivylyn on a blind date. A mutual friend set it up after hearing John comment how pretty she was as he strolled past her in town. They sat up talking until four in the morning. He had a slight build with penetrating blue eyes. He had a passion for gardening and worked in a hardware store. When they got married, they spent their honeymoon in a cabin on Jennings Creek without a care in the world. They promised each other to spend some quiet time alone every day thinking about one another. John at 8:00 and Ivylyn at 5:00.

Weldon Rosazza, whose surname came from an Italian town, had all the luck with the ladies. Both at home and abroad. He spent a short time in Washington D.C. as a child and had an obsessively neat appearance. Because of this, he was considered the most sophisticated of the Bedford Boys. He and John Clifton would run around in Ivybridge in southern England winning the hearts of many young English ladies. His buddy John Clifton, is described by his high school classmates as nice, quiet, and handsome. Many in Bedford knew John because he used to deliver the Bedford Bulletin to local homes as a boy. He met a girl while training in England and got engaged. He was hit by a burst of German gunfire as the ramp dropped on his landing craft. His last words were, “Lt. Nance, I’ve been hit!”

Gordon “Henry” White had a passion for farming. Every day after school, he would rush home and change into his work clothes. Stuffing apples into his pockets as snacks, he labored until nightfall on his family’s farm. It is said that he liked to plow. That he just liked being out on the farm, in the dirt. His siblings remember him as a leader in the family. He took them out hunting, fishing, and trapping. He also taught them the game of baseball. It’s not known how he died, but his family speculates he died in the water. Many of his personal belongings that were returned to them had been wet.

Wallace Carter grew up poor. Most did in and around Bedford those days, but he always seemed to have a thick wallet and an extra dime for the movies. It wasn’t his employment that gave his wallet the extra width, though. His job at the Bedford pool hall didn’t pay much. But it did provide the opportunity to play eight-ball, a game in which his winnings outpaced his wages. Pool wasn’t the only game he played though. He was a popular player for the Mud Alley Wildcat baseball team. A team that drew its players from the poorest streets in town.

Jack Powers stood over six feet tall and two hundred pounds. All of it muscle. But as physically imposing as he was, he is remembered as a big-hearted man who loved to dance and play guitar. He practiced every day and even recorded some songs. But the old wax records haven’t survived the passage of time. Jack could jitterbug as well as anyone and many Bedford ladies enjoyed a spin around the dance floor with him. Once Jack accidentally stepped on one of his sister’s kittens. He was so heartbroken over it, that he gave her his skates.

In 1938, 17-year-old Leslie “Dickie” Abbott begged his father to sign papers allowing him to join the National Guard. His father relented, although reluctantly. Dickie was raised mostly by his grandmother and shared her sense of humor. A joke was always on his lips and he loved to laugh. He was a really fun guy. He would ride around town on horseback. Smoking a hand-rolled cigarette from tobacco he grew himself. He was wholly committed to his large, God-fearing family. He cherished sitting with them feasting on fresh buttermilk, cornbread, and fried chicken. The perfect meal after a long day in the fields.

Nicholas Gillaspie, like so many from the area, grew up on a farm. He was tall with light-colored hair. Quiet and dependable, he was known around Bedford for his impeccable manners and constant smile. He was an avid baseball player and fisherman before the war, but he was particularly skilled at Rook. He played it all the time. Nicholas was also a prolific letter writer. He wrote to more than a dozen friends and neighbors. All loved to receive his witty letters and postcards from England. So when the letters stopped coming after D-Day, everyone was worried.

After graduation, many found employment at Hampton Mills, including Clifton Lee. A shy and gentle man, he was well-liked and very friendly. He loved his family and spoke of them often. He was shot while trying to swim to shore on D-Day.

Remarkably close to his mother, John “Jack” Reynolds begged her to let him join the National Guard. He wanted to serve with his friends. He grew up on a farm in a large family. He had seven siblings, the youngest of whom was born a year after he died in Normandy. His mother would spend Sunday afternoons reading his letters over and over and over again. On the beach that day, he dropped to his knees and brought up his rifle to search for the enemy. In the next moment, he fell forward. Dead. His mother felt like a part of her died with Jack, but she vowed to bring him home. “I’m not leaving my boy over there. France may take my boy away from me, but France is not keeping him!”

For these men, there would be no more gatherings at Green’s Drug Store at the corner of North Bridge and Main. No opportunities to share their stories of heroism with the younger boys. No longer could they enjoy the “best strawberry ice cream float” at the soda fountain in the back. Green’s was the hub of the town. Every one of the Bedford Boys came through here. Some worked here when they were younger. One couple had a blind date here. But for all the happy memories at Green’s, it was also the location for incredible sadness. This is where Elizabeth Tease worked. As the Western Union telegraphs came in, it was she that received them. Every morning the Sheriff, doctor, cab driver, and others would meet here for coffee. And on the morning of Monday, July 17th, 1944, the first of what would eventually be 19 telegraphs came in. Each carrying the devastating news of Bedford’s war dead. Those gathered in Greens would leave to deliver the news to the families.

The local newspaper, while eulogizing the dead, said “The names of sons of neighbors living next door or on the adjoining farm may be found in this list. Or there may be the names of boys who sat next to some of the readers at school or lads who sold groceries over the counter at the local store.”

Everyone in this tight-knit community in the Blue Ridge Mountains was affected by the news. Everybody knew somebody. 19 men were killed in the first minutes of the D-Day landings. 3 more would be killed during the Normandy campaign. No other American community paid this high a price for freedom on that day. Bedford lost more men per capita than anywhere else.

The Great Depression hit Bedford hard. When the enlisted men reported for active duty, it put an even greater strain on the small farming community. When Dickie Overstreet left for World War II, his father couldn’t maintain the family’s farm without him. He had to work in a shipyard to keep his 11 children fed. In 1938, joining the Guard had less to do with patriotism and more to do with economics. Many of the men who signed up, did so for the $1 a day for drills. One dollar was a lot of money back then. Plus, during their annual two-week drills, that was an extra $15 a month. The new uniforms were a nice incentive, as well. Crisp, new uniforms were a welcomed change from the dirty, hand-me-down clothes synonymous with the Great Depression era. Regardless of the motivations, though, each man served our country. Unsure of what the future held.

This small town in central Virginia holds a special place in American history. This is the image of home that those boys carried with them. On the lonely nights in a far-off land when they were scared. Bedford held the dreams of a life they fought to return to. To the lives they put on hold to answer the call.

Bedford, like so many cities and towns across America, gave her young men to fight fascism. But why did sorrow have to fall so heavily on her and not some other town? Why did she have to pay such a price? These questions may never be fully answered. But these men fought for each other. They fought for their neighbors and for those they would never meet. They fought for you and me. Many years after the fact, Roy Stevens said, “You know, us Bedford Boys, we competed to be in the first wave. We wanted to be there. We wanted to be the first on the beach. We got our wish.”

Read more about the D-Day National Memorial located in Bedford here.