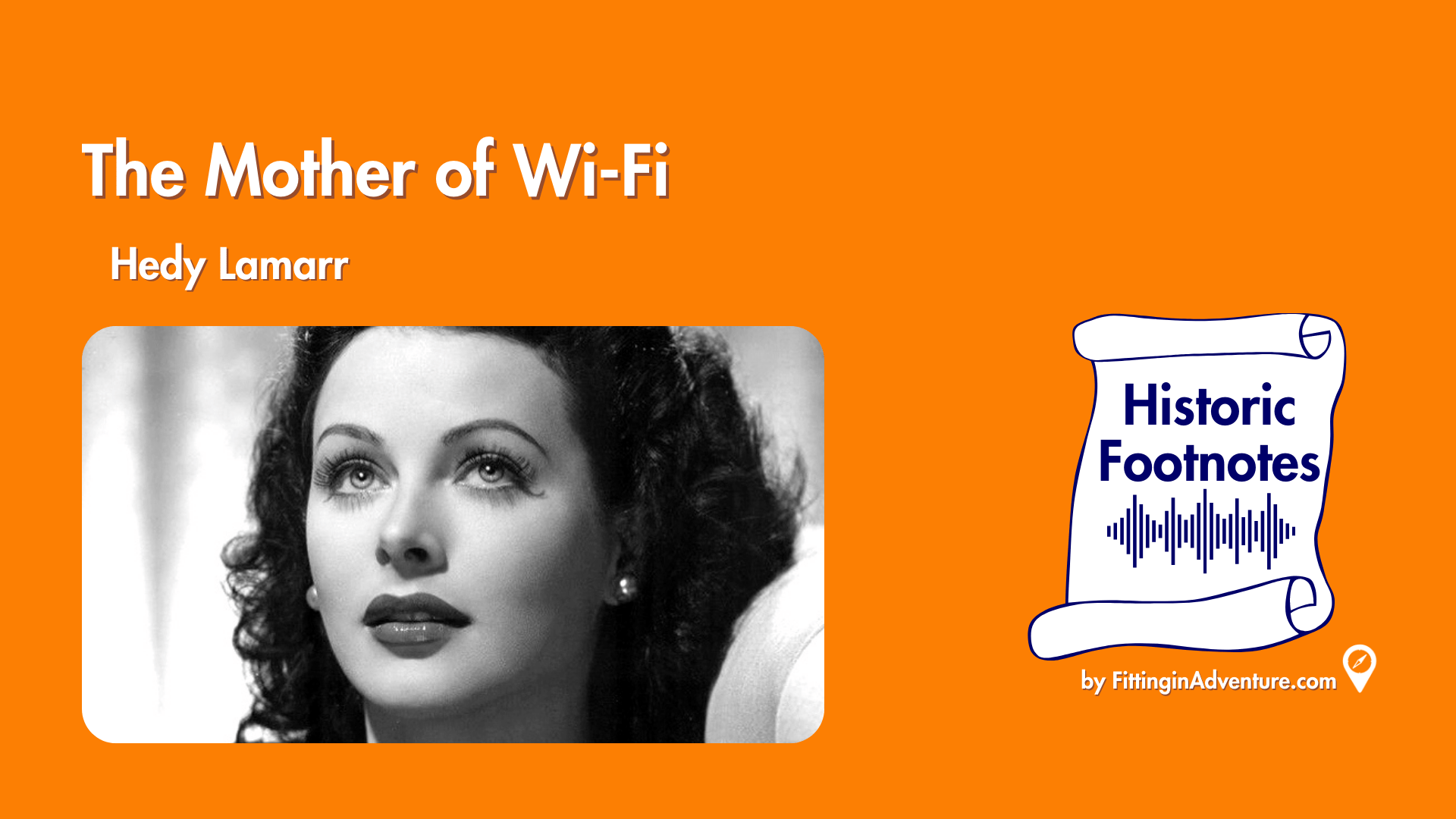

Do you know “The Mother of Wi-Fi”? Or, which Hollywood actress helped pioneer the technology enabling you to listen to this podcast? Or, if you’re driving, the GPS navigates you to your destination. Each of these technological advancements was built upon the “frequency hopping” communications system developed, in part, by a film star of Hollywood’s Golden Age. A woman that Howard Hughes referred to as “a genius”! This star’s name was Hedy Lamarr, but she was also so much more.

Disclosure: Some links on our site are affiliate links. If you purchase a linked item, we will make a commission, at no extra charge to you.

She was born on November 9th, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. She was extremely close with her father, a bank director, and curious man, who taught her to look at the world through open eyes. They would take long walks while they discussed how different machines worked. Like street cars or the printing press. At only 5 years old, she would be found taking apart and reassembling her music box. Just to see how it operated. She was introduced to the arts by her mother, a concert pianist, who enrolled her in both ballet and piano lessons at an early age.

Hedy’s brilliant mind was ignored, but not her beauty when she was discovered by director Max Reinhardt at only 16 years old. Studying acting under him in Berlin, she earned her first film role by 1930, but it wasn’t until the 1932s controversial film, Ecstasy, that she gained name recognition as an actress.

An Austrian munitions dealer became infatuated with her after seeing her in the play Sissy. They married in 1933, but the marriage was destined to be short-lived. She once said, “I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife … He was the absolute monarch in his marriage … I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.”

She was forced to smile and play host among her husband’s friends and scandalous business partners. Some of which were associated with the Nazi Party. Terribly unhappy, she escaped him and fled to London in 1937 and took with her the knowledge she learned from dinner-table conversations regarding wartime weaponry.

While in London, Hedy Lamarr was introduced to Louis B. Mayer, of MGM, where she secured her ticket to Hollywood. Once there, she mystified American audiences with her grace, beauty, and accent. It was here that she also met billionaire Howard Hughes.

They dated briefly, but she was more fascinated with his desire for innovation. Her scientific mind was suppressed in Hollywood but Hughes fueled her innovative spirit and gave her equipment to use in her trailer on-set. Hughes took her to his aircraft factories, explaining the processes and introducing her to the scientists behind the scenes. Hughes wanted to create faster planes that could be sold to the military, inspiring Lamarr. She bought a book of fish and a book of birds. She looked at the fastest of each kind and, combining the fins of the fastest fish and the wings of the fastest bird, sketched a new wing design for Hughes’ planes. When Hughes looked at the new design, he told her, “You’re a genius!”

But her most significant invention came as the United States readied for World War II. In 1940, she met George Antheil at a dinner party. While known for his writing, film scores, and experimental music compositions, he shared the same inventive spirit as Lamarr. They talked about a lot of topics, but their greatest concern was the looming war. Lamarr remarked that “she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state.”

Because of her marriage, she had knowledge of munitions and weaponry that could be very beneficial. So the two began to develop ideas to combat the Axis Powers. They came up with a new communication system with the intention of guiding torpedoes to their targets. The system used frequency hopping among radio waves. “Frequency hopping” was an ingenious way of switching between radio frequencies in order to avoid a signal being jammed. By manipulating radio frequencies at irregular intervals between transmission and reception, the invention formed an unbreakable code that could prevent radio waves from being intercepted.

Lamarr and Antheil were awarded a patent in August 1942, for their invention, and donated the technology to the US military to help fight the Nazis. Unfortunately, it was dismissed at the time and its significance wouldn’t be realized until decades later when it was used by the Navy during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

It would then go on to be used in a wide range of military applications, but it was the “spread spectrum” technology they developed that would form the basis of modern wireless communication technology that we take for granted today.

Sadly, the patent expired before she ever saw a penny from it. It wasn’t until Lamarr’s later years that she received any awards for her invention. The Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly awarded Lamarr and Antheil with their Pioneer Award in 1997. She also became the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. And was also inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Hedy Lamarr died on January 19, 2000, in her Florida home. And while she will likely always be remembered more for her spectacular beauty than for her technological contributions, which are usually treated as an intriguing footnote, they form the basis for much of the technology we rely on today. “My face has been my misfortune,” she once observed, describing it as “a mask I cannot remove. I must live with it. I curse it.”