In the early morning of April 9th, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee clings to the belief the war was not over. Those under Lee’s command lined up for battle west of the village of Appomattox Court House. His hope is there’s only a thin line of Union cavalry stopping him from finding supplies and rations. Then, turning south, he plans to march to North Carolina to continue the fight. This plan, and the Southern war effort, are thwarted by Grant and his Army.

Disclosure: Some links on our site are affiliate links. If you purchase a linked item, we will make a commission, at no extra charge to you.

Table of Contents

Facts about Appomattox

- In the First Battle of Manassas, Virginia, Wilmer McLean’s home serves as Headquarters. Afterward, he moved to Appomattox Court House to avoid the war. He stated, “The war started in my front yard and ended in my front parlor.”

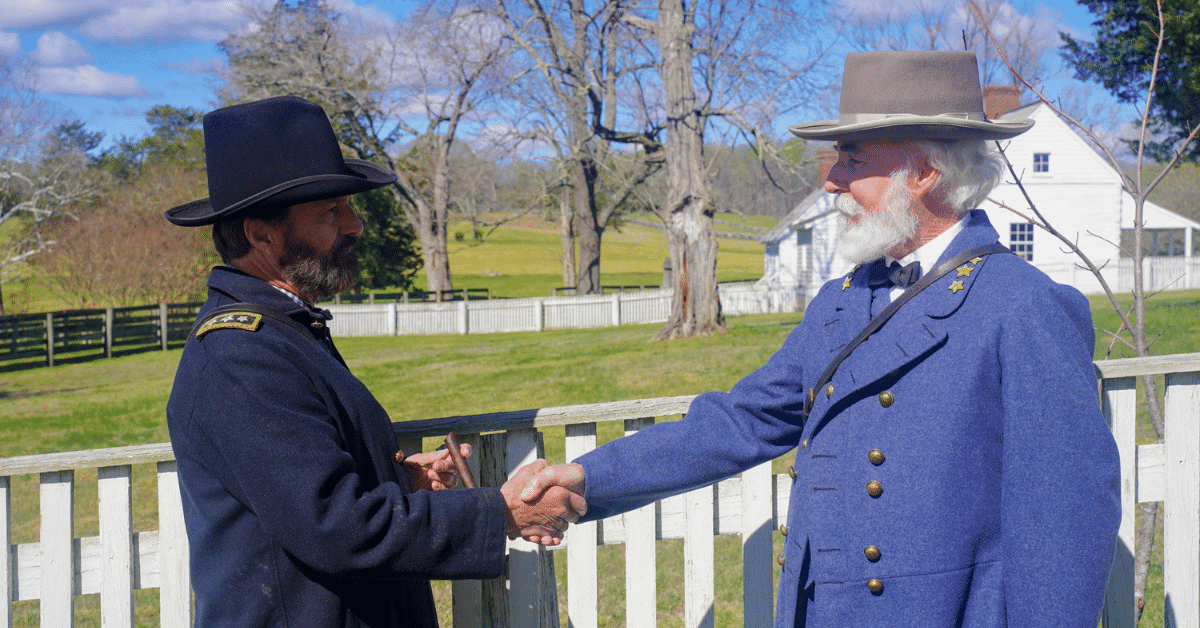

- Union troops saluted their former enemies at the surrender ceremony. Witnesses reported interactions between the former opposing Armies. They are kind and friendly, for the most part.

- The surrender did not end the war with the final battle taking place a little over a month later, in Texas.

- Grant agreed to parole the entire Army of Northern Virginia. He even offered food to the rebels as they were desperately low on rations.

- Lee surrendered, in part, to avoid unnecessary destruction of the South.

For the past week, General Grant had impeded Lee’s plans to turn south. As a result, he had finally gotten ahead of Southern forces at Appomattox Court House. A few days prior, Lee suffered a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek. About a quarter of his Army was forced to surrender. Grant asked Lee to surrender. Telling him “further effusion of blood” would be solely his responsibility. Lee clung to the hope he could still escape Grant and declined to surrender. Instead, he asked for a peace agreement. Grant replied he could not discuss a peace agreement. But could consider a military surrender. Two days later, following an early morning battle on April 9th, Lee realized he was cornered. He then asked to discuss the terms of surrender. Not all under Lee’s command agreed with the surrender. General Edward Alexander suggested Lee disperse his Army. To tell them to regroup with General Johnston, in North Carolina. Or return to their states and continue fighting. Lee rejected this advice. He explained the men would be without rations and supplies. And under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal to survive. In effect, being a band of marauders. This could cause a disaster from which the country would take years to recover.

There is nothing left for me to do but go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.

General Robert E. Lee

Lee sent two letters to Grant to discuss surrender. One east through Union General George Meade’s lines. And one southwest through Union General Philip Sheridan’s lines in an effort to reach him. Grant had been riding all morning to reach Sheridan’s forces when the letter caught up with him. Grant sent one of his staff officers, General Orville Babcock, with a reply. He agreed to meet and told Lee to choose a meeting spot. Lee sent his aide, Colonel Charles Marshall to the village to find a suitable home for the meeting. Details are sparse, but it seems Wilmer McLean’s home was chosen because he’s the first owner Marshall encountered. McLean first showed Marshall an abandoned, unfurnished building. Marshall rejected this as unsuitable. Only then did McLean offer up his home.

Lee arrived first. Sometime after one o’clock in the afternoon and waited with Marshall and Babcock. Grant and his staff arrived about 30 minutes later. Grant was uncertain how to bring up the subject. Instead, he brought up the Mexican-American War and the brief meeting the two had then. After a short while, Lee said they should get to the business at hand. Grant took out his order book and quickly wrote the terms. The terms already outlined in letters the two had exchanged in the previous two days. Grant’s terms to Lee were a mere five short sentences. Lee’s response was a very terse three. Different from what you would expect, there was no formal surrender document at the time.

Other than Colonel Marshall, Lee sat alone in the front parlor of Wilmer McLean’s home. Grant was accompanied by about a half dozen of his staff. Around a dozen other Union officers entered for brief periods of time. Including President Lincoln’s eldest son, Captain Robert Todd Lincoln. Only a few left details about what took place that afternoon. And while there are some disagreements in the details, there are many consistencies.

The main term of the surrender is parole. Confederates would be paroled after surrendering their weapons. Along with other military property. If the former soldiers promised not to again take up arms, the U.S. Government would not prosecute. Confederate officers were allowed to keep their sidearms and horses. This was to avoid unnecessary humiliation. Lee, who had expected to be taken prisoner, was relieved. He had dressed in his finest uniform to be in proper form and “make his best appearance.”

The two Generals agreed to appoint three officers from each Army. They would act as a “commission” for the surrender. This commission would work out the details of parole passes. Returning Union POWs. And sending rations to the Confederate forces.

By 3 o’clock, the formal letters were drawn up after the agreement of terms were signed. As he left the McLean home, Lee paused at the top of the steps. According to one of Grant’s aides, he “smote” his hands together three times. Smote is forcefully striking your hands together. Grant and his staff removed their hats in a respectful, farewell gesture. Lee returned the gesture before riding off down the road. Union forces began cheering. Grant had it stopped immediately.

The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult in their downfall.

General Ulysses S Grant

Grant proceeded to send a telegraph back to President Lincoln. Stating that Lee had surrendered. The following day, General Grant again met with Lee. He wanted Lee to persuade other Confederate forces to surrender, but he refused. Also, Lee directed Colonel Marshall to draft a farewell address to his Army. In it, he took responsibility for the surrender to spare further suffering to his men. He praised his men for their “consistency and devotion.”

Lee stayed in Appomattox until April 12th, the day of the formal Infantry surrender. Four years to the day of the firing at Fort Sumter, starting the conflict. Sadly, the victory is short-lived for President Lincoln. He is assassinated two days later by John Wilkes Booth. The rest of the country struggles through a series of more surrenders. After Lee surrenders at Appomattox, the Confederate government falls apart. And on May 10th, the capture of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Each of these events is claimed to be the “real” end of the war.

Any one of these can be viewed as the end of the war. But regardless of what event you choose to signify an end, the cost of the Civil War is unprecedented. It is our country’s bloodiest conflict. An estimated 1.5 million are reported as casualties during the war. Roughly 2% of the population lost their lives in the line of duty. An estimated 620,000 men. Nearly as many die in captivity as were killed in Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands perish to disease. Entire communities are devastated by the loss.

But, after four years of the most brutal bloodshed our country has ever faced, it was over. In a civilians front parlor, in a mere eight sentences, our country was once again united.

The war started in my front yard and ended in my front parlor.

Wilmer McClean

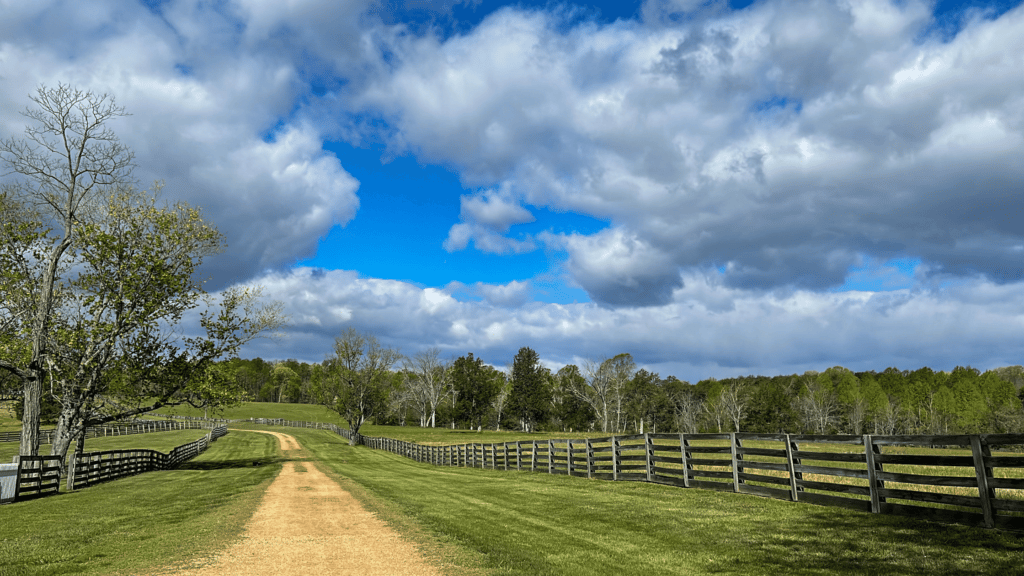

Visiting Appomattox Courthouse National Historic Park in Virginia

The park is free to visit and includes walking trails, exhibits, and guided programs.

Check the park site for hours and special event information.

While you are in the area, head over to Bedford to enjoy the National D-Day Memorial, Bedford Boys Tribute Center, and more activities in central Virginia.