“Here we shall plant our stakes and not abandon them until we drive these red-coat rascals into the river, or the swamp!”

Major General Andrew Jackson

In the cold, foggy morning of January 8th, 1815, a future President, a motley crew of militiamen, frontiersmen, slaves, Choctaw Indians, and even pirates, will face off against one of the most powerful armies in the world…and claim victory.

Disclosure: Some links on our site are affiliate links. If you purchase a linked item, we will make a commission, at no extra charge to you.

Thirty-six years after declaring independence from Great Britain, Americans once again declare war against the British. The United States is angered by English interference with trade causing the economy to suffer greatly. Additionally, the impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy, and the belief that Great Britain is aiding and supplying Native Americans to fend off settlers moving to the west, further angers the Americans. So, on June 18th, 1812, the young country went to war with England. After defeating Napoleon in early 1814, Great Britain redoubled its efforts against the former colonies. In what is hoped to be the wars’ final blow, they launch a three-pronged invasion of the United States. Two of the incursions had already been repulsed; the Battle of Plattsburgh from September 6th – 11th, and the Battle of Baltimore from September 12th – 14th, 1814. The latter of which is witnessed by Francis Scott Key, inspiring him to write “The Star-Spangled Banner”. The last will be an assault on the city of New Orleans. This vital seaport is considered the gateway to the new western territories gained with the Louisiana Purchase. Learning of the planned assault, Major General Andrew Jackson leaves Mobile, Alabama for the city on November 22nd. Arriving on December 1st, Jackson hastens to the city’s defense. Finding little more than 1,000 men and a mere two ships, Jackson declares martial law, requiring every weapon and able-bodied man in the city to come to its’ defense.

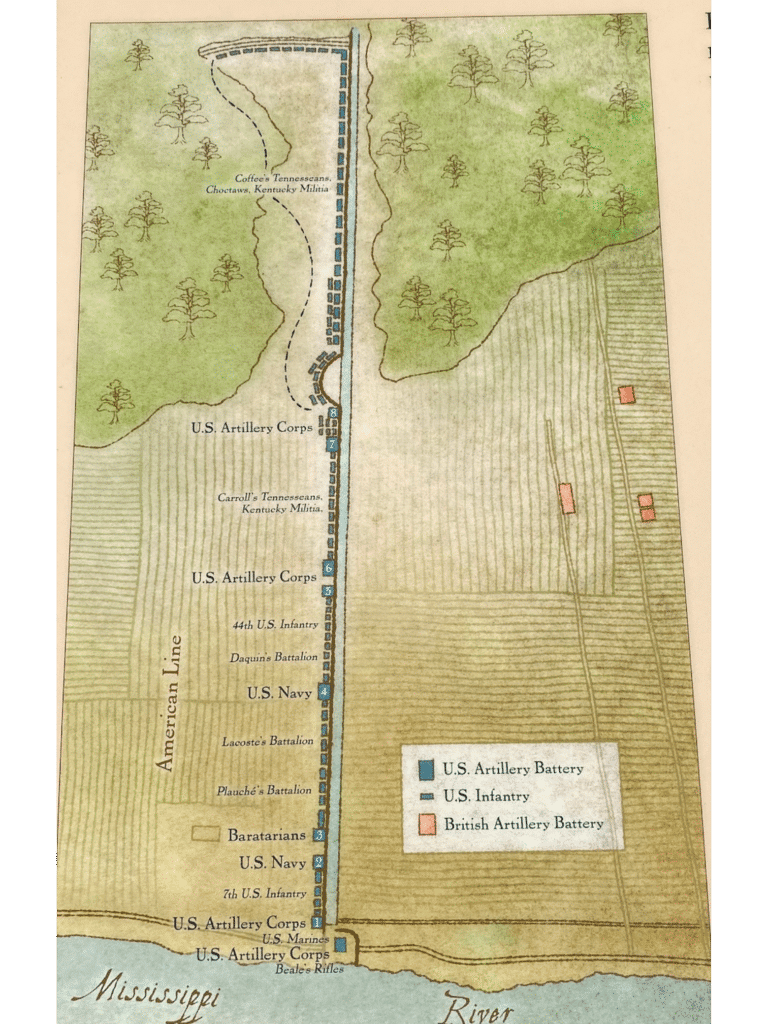

The city’s defense is primarily made up of volunteers. Grouped into battalions, they are the Uniformed Battalion of Orleans Volunteers and the First and Second Battalion of Free Men of Color. Of the Uniformed Battalion, four of the five companies are composed of white Creoles from Louisiana and Saint Domingue (now Haiti). The fifth company is composed of native and naturalized white Americans or non-Creoles. The First Battalion of Free Men of Color, led by Major Pierre LaCoste, is composed of black Louisiana Creoles. The Second Battalion of Free Men of Color, led by Majors Louis D’Aquin and Joseph Savary, is composed primarily of Saint Dominque Creoles.

Also serving are two semi-independent companies. The Company of New Orleans Riflemen, a sharpshooter company of 68 non-Creoles, is led by Captain Thomas J. Beale. They will come to be known as Beale’s Rifles. The second of these companies are the sailors of Barataria, pirates that served with Lafitte. These men serve as gun crews under Captains Dominique Youx and Renato Beluche, themselves pirates under Lafitte. Interspersed between these are slaves and Native Americans. Together, they will defeat the larger and superior force of British veterans.

If Britain can seize New Orleans, they will gain dominion over the Mississippi River, controlling the American South’s trade. To aid in this, Jackson offers pirate Jean Lafitte a treasure trove of items. The offer included land in British-controlled North America, $30,000 cash, and the rank of Captain in the Royal Navy. With the only requirement being he and his men join the Americans. Lafitte asks for time to consider the offer and promptly contacts the Americans. In providing proof of his claims, he adds documents to the letter he sends. Jackson meets with Jean Lafitte, in either (Maspero’s) Exchange Coffee House or The Old Absinthe House, to discuss aiding Jackson in battle. (Both locations claim to have housed the meeting, even taking it into Louisiana courts.) In the final deal, Lafitte and any of his men who serve in battle will receive a pardon for piracy from America. At Lafitte’s encouragement, many join the New Orleans militia, serve aboard ships, and form three artillery companies.

In late December, Jackson visits the Rodriquez Canal, a small drainage ditch cutting across Chalmette Plantation, a few miles east of the city. Knowing the British commander General Pakenham will march his men across wide-open terrain. Jackson constructed a nearly 1500-yard rampart on the eastern bank of the river, parallel with the canal, using logs, earth, and cotton bales. Realizing the American lines are too short, Lafitte recommends extending the line to the swamp on the left of the field. Jackson orders it done. This became known as “Line Jackson”. For added insurance, Jackson orders the canal widened to serve as a moat with the removed dirt used in the rampart. This is the defensive position Jackson, himself, will command. At his disposal are 4,000 men with 12 artillery pieces grouped into 8 batteries.

Across the river on the west bank, Brigadier General David Morgan commands another 1,000 men and 16 cannons. Anchored along the right bank sits the USS Louisiana, a sloop outfitted with sixteen 24-pounder guns. The ship fires on advancing British troops on several different occasions leading up to the main battle. When British troops advance beyond the range of Louisiana’s guns, crew members wade ashore with mooring lines and tow the ship upriver against the current to re-engage.

The British plan to deal with “Line Jackson ” relies heavily on the use of ladders and fascines. A fascine is a long bundle of sticks bound together. The fascines will be used to cross the Rodriguez Canal and the ladders to scale the rampart. Unfortunately for the British, Lieutenant Colonel Mullins (whose regiment was responsible for bringing these essential supplies forward) loses track of these.

“If I live until tomorrow, I will hang Colonel Mullins from one of these trees!”

British Major General Gibbs

At 5 in the morning, British Commander Major General Pakenham orders his men forward. The battle has begun. It goes badly for the British from the start. As the British advance, they soon discover they neglected to bring the fascines and ladders. As some return to retrieve the items, others ineffectively return fire. They are sitting ducks within range of American artillery. Those who do manage to advance and cross the canal find it impossible to move forward any further, suffering heavy casualties.

British losses are great. Losing Major Generals Pakenham, Keane, and Gibbs, and large numbers of other field grade officers. The Americans are outnumbered approximately 2-1, but decisively defeat the British force. British casualties are reported to be 858 killed, 2,468 wounded, and 484 missing or captured. The Americans suffered 7 dead, 12 wounded, and 19 missing or captured. The battle had lasted a little over two hours. The field in front of “Line Jackson” is littered with thousands of dead and dying men.

“A space of ground extending from the ditch of our lines to that on which the enemy drew up his troops, two hundred and fifty yards in length, by about two hundred yards in breadth, was literally covered with men, either dead or severely wounded. About forty men were killed in the ditch, up to which they had advanced, and about the same number were there made prisoner.”

Major A. LaCarriere Latour

On the date of the battle, a peace agreement had been reached in Ghent, Belgium, but had not yet been ratified. Even so, word of any such agreement would take weeks to reach American shores from Europe. On February 16th, 1815, America’s “Second War of Independence” ended. The treaty accomplishes none of the original objectives which precipitated the war, in the first place, but reports of General Jackson’s victory and a peace agreement prompt great celebrations.

Visiting the Chalmette Battlefield National Park

Located just down the river from New Orleans in the Jean Lafitte National Preserve sits the opened field where the Battle of New Orleans took place in 1815. The entrance is open to the public and the visitor’s center is open daily. Accessible walking trails are available throughout the park with a drive loop around the field.

Check their events for reenactment information.