On April 5th, 1839, Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina. His mother, Lydia Polite, was owned by John McKee. McKee may have been Robert’s father, but it also may have been his son, Henry. It may have even been the plantation manager, Patrick Smalls. While it’s not clear who his father is, it is clear that the McKee family favored Robert over the other enslaved children. So much so, that his mother feared he would grow into adulthood without grasping the horrors of slavery. To make sure he understood, she arranged for him to work in the fields. To see how the enslaved were treated. This plan may have worked too well as it made Robert defiant. So defiant that his mother feared for his safety. Because of this, he frequently found himself in the Beaufort County Jail.

Disclosure: Some links on our site are affiliate links. If you purchase a linked item, we will make a commission, at no extra charge to you.

His mother asked the McKees to allow Robert to be sent to Charleston. And again, her request was granted. By the time he turned 19, Robert had worked several jobs around the city and especially, the water. Of his wages, he was allowed to keep one dollar a week with the rest going to his owner. But more valuable than money was the education he received on the water. No one knew Charleston Harbor better than Robert Smalls.

While working in Charleston, he met and fell in love with his wife Hannah. Enslaved by the Kingman family working at the Charleston Hotel. With their owners’ permission, Robert and Hannah moved into a small apartment and had two children. Elizabeth and Robert Jr. Knowing this was no guarantee of a permanent union, Robert attempted to buy Hannah’s freedom from the Kingman family. They agreed, but at a steep price; $800! He had $100, but who knows how long it would take to save the other $700. They knew as long as they were in chains, they could never be sure of their future together. Robert promised Hannah they would one day escape slavery.

When the war broke out, Robert was assigned to the Planter, a Confederate military cargo ship. Robert did his job superbly. Piloting the ship around the harbor with great skill and earning the confidence and trust of the black crew and the three white officers. Having earned the trust of the officers and crew, Robert devised a plan of escape. To the Confederates, Union ships enforcing a blockade of southern ports were another example of the North’s enslavement of the South. But to real enslaved people like Robert, these ships symbolized the promise of freedom.

Under orders from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, Navy Commanders were accepting runaways as contraband for months. While Robert couldn’t buy his family’s freedom on land, he could win it by sea. He told Hannah to be ready when the opportunity presented itself.

And the opportunity came on the night of May 12th. Exactly one full one year and one month after the first shots of the war were fired at Fort Sumter. As the three white officers left to sleep ashore, Robert told his plan to the crew. Of the crew, two chose to stay behind because of the extreme danger. Because Robert and the rest had no intention of being taken alive. Either they escaped, or they fought with whatever guns and ammunition they had. When all else was lost they would sink the ship, if necessary. Failure or detection meant certain death.

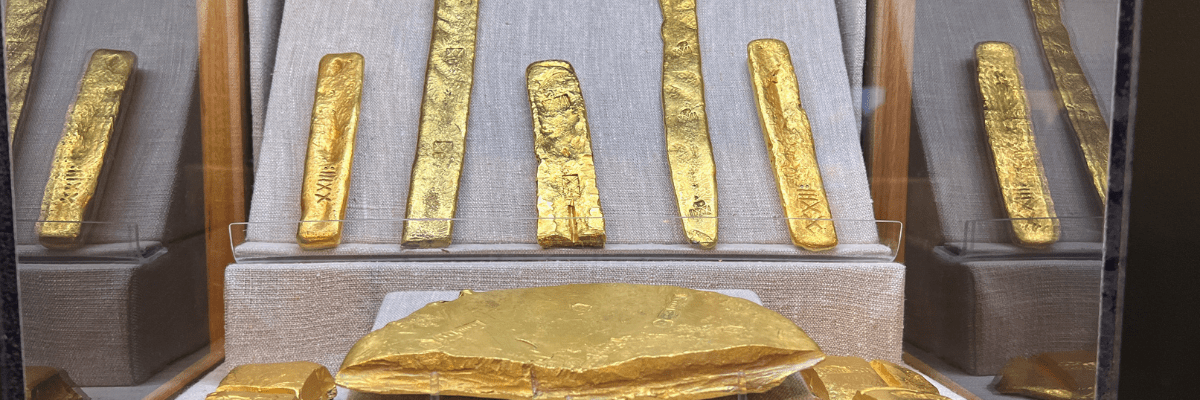

After two weeks of supplying the islands in Charleston’s harbor, the Planter is heavily armed. 200 rounds of ammunition, a 32-pound pivot gun, a 24-pound Howitzer, and four other guns. As the three officers disembarked for the night, they left the 8 crewmembers aboard. One of which is Robert, who has been sailing these waters since he was a teenager. Now, at 22, Robert is presented with the chance he has been waiting for. He will earn his family’s freedom…or die trying.

At 2 am, Robert dons the Captain’s straw hat and orders the crew to stoke the boiler and hoist the South Carolina and Confederate flags. They ease out of the dock in full view of Confederate General Ripley’s headquarters. They pause at the West Atlantic Wharf to pick up Robert’s family, along with 4 other women, 3 men, and a child. From the ship’s pilot house, Robert blows the whistle as they pass Confederate Forts Johnson and Sumter. He not only knows what signals to flash, he even crosses his arms like the Captain so, in the early morning shadows, but he also passes convincingly as him.

It isn’t until after the Planter passes out of Confederate gun range is the alarm sounded and the plan is discovered. As they approach the Union blockade, Robert orders the crew to lower the South Carolina and rebel flags and raise a white bedsheet his wife brought aboard. The USS Onward opens her gun ports and readies to fire. Just as they are about to open fire, someone shouts “I see something that looks like a white flag!” As Robert and the rest realize they won’t be fired upon, all rush out on deck. Singing, dancing, whistling, and jumping. As they came closer and under the stern of the Onward, Robert stepped forward, removed the straw hat, and said “Good morning Sir. I’ve brought you some of the United States’ old guns, Sir!” Those aboard the Planter are now free.

He may not have had the $700 needed to buy his family’s freedom, but now, because of his bravery and skill, they are free. Congress passes a private bill allowing the Navy to appraise the ship and award half of the proceeds to Robert and his crew. He receives $1500 personally. Enough to buy his former owner’s house in Beaufort after the war.

Robert is regarded as a hero in the North. He personally lobbied Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to begin enlisting black soldiers. When President Lincoln opened the military to blacks, Robert was said to have enlisted 5000 himself. In October, he returned as the pilot of the Planter as part of the South Atlantic Blocking Squadron. According to the 1883 Naval Affairs Committee report, he was part of 17 different military actions. Including the April 7th, 1863 assault of Fort Sumter. Two months later during the attack at Folly Island Creek, he assumed command of the Planter when the white Captain hid in the coal bunker. Because of his actions, he was promoted to Captain, himself. From December 1863 on, he earned $150 per month, making him one of the highest-paid black soldiers of the war. When the war ended, Robert stood aboard the Planter during a ceremony in Charleston Harbor. Nearly three years after that fateful night when he set in motion a daring plan for his family’s freedom.

After the war, Robert continued to push the boundaries of freedom as a first-generation black politician. He served in the South Carolina State Assembly and Senate and for 5 terms in the US House of Representatives. Sadly, he also viewed the South try to recreate slavery through Black Codes and Jim Crow laws. But despite this, Robert Smalls refused to be pessimistic. Telling the South Carolina Legislature “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Robert passed away on February 23rd, 1915, in the same house behind which he had been born enslaved.